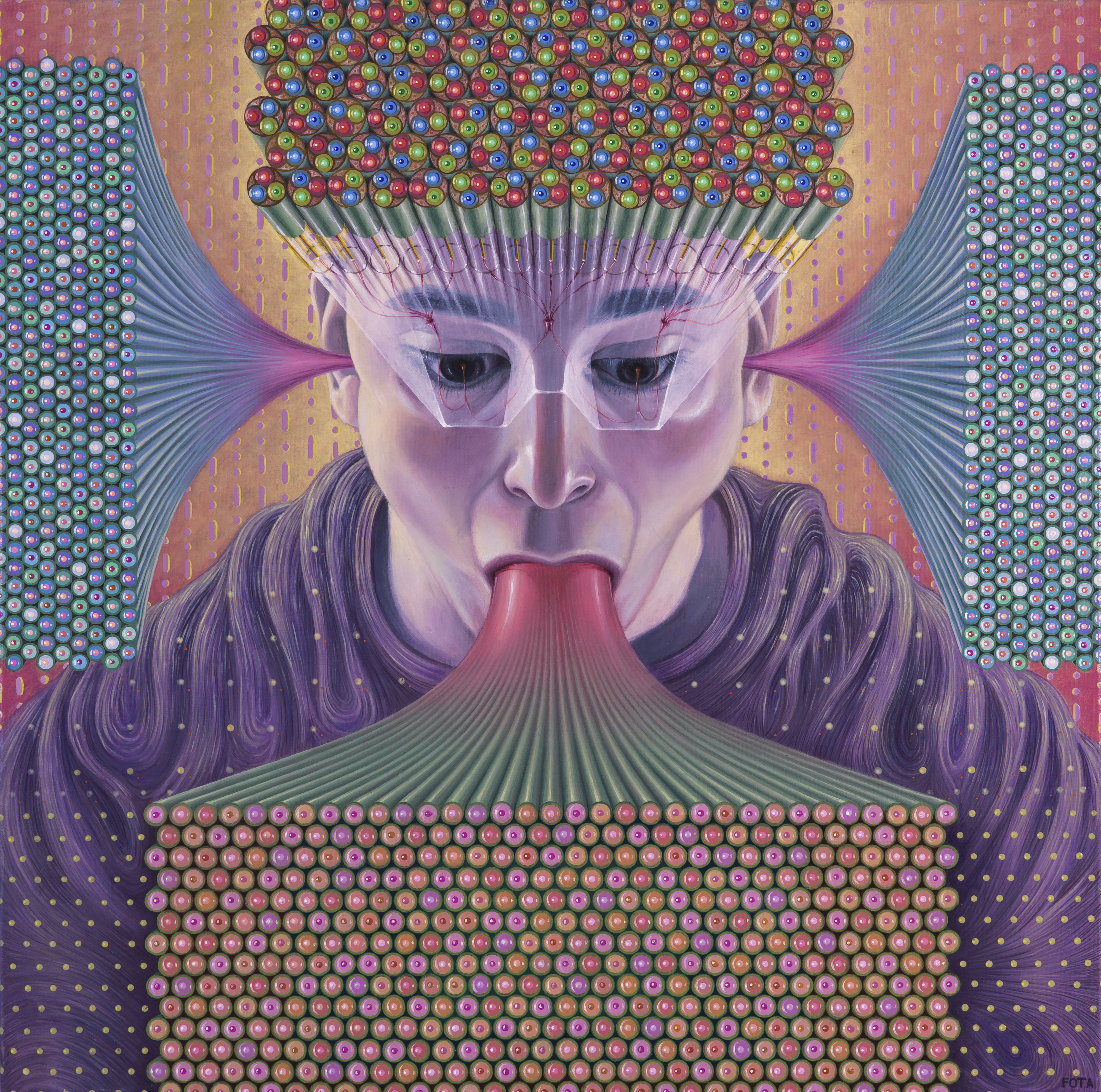

The flemish technique, an oil painting technique that characterizes most, if not all, of Victor Fota‘s portfolio, uncannily resembles my own process in essay-writing. Starting by constructing the bone, and then adding, bit by bit, layers of detail that delve into deeper a narrative – I weave my essays with careful gestures of the pen, while Fota finishes his with a paintbrush. It is a highly meticulous and carefully planned process, where though hints of spontaneity can be seen in the beginning sketches, they quickly become increasingly controlled and elaborate as more layers are added. Fota introduces a world that marries quantum mechanics and technology together with this calculated technique, which is inspired by his background in art history. His works seemingly engage his audience in a puzzle game that requires close attention in order to figure out his message. In this interview, Fota not only talks of the tips and tricks to oil painting and the flemish technique but also give pointers to how art students should manage a balance between their creative integrity and the commercial realm.

i) The themes of your work range from quantum mechanics and physical reality, to the human imagination and the surreal realm. Essentially, are you marrying what a lot of people would consider “polar opposite”, which is art and science?

I don’t think that art should be dissociated from any subject. It can be about anything the artist wants to illustrate. The association between the artist, their feelings and subjective views is just a stereotype. Art today is more about science because science is a lot more present in our lives than it was in the past. We see our reality through facts rather than spirituality, which was the main theme of art in the past. For me, the most interesting things in life are the mysterious. That’s why I find science to be so interesting because it researches into the unknown and gives credible results. My first series of paintings, Cosmogony, was just about reinterpreting theories that are already established in physics. So, it was like an exercise of understanding science through painting an image. For my second series, Human Extension, I tackled more into technology – how it affected me personally, as well as other people.

ii) Since you graduated with an Art History major in Conservation-Restoration, are there any alternative historical oil painting techniques that you would like to incorporate into your future works, and why?

I experimented with all of the major techniques of oil painting – flemish, grisaille, italian, a la prima, even tempera, which is a semi-oil technique, but I find that a combination of the flemish technique using a grisaille underpainting suits my style of work best. The flemish style is characterized by successive layers of glazes over a monochrome underpainting, which is usually done with washes of sienna. Instead of the sienna washes, I use the grisaille, which is a black and white underpainting that allows a better control over the values (lights and shadows).

iii) Your main medium is oil, and you work with the “old flemish method of rigid forms and successive glazes of paint” which involves a build-up of monochromatic under-layers and tonal layers with more detail on top. Do you enjoy working in such a carefully thought-out process, and how do you think this is reflected in your pieces?

I enjoy planning very much, and I like to stick with my initial sketch and idea as much as possible. I get spontaneous enough when I am sketching. That’s why this technique is best suited for my needs. At the moment, I am getting a bit looser with my brushwork, but I don’t think it ends up becoming messy in the end because it’s much more controlled now as it was in my past works. The final result is a digital-like painting, which can be impressive for people who understand the meticulous work that needs to be put in for it to end up like this. For other people, this “perfection” is exactly what is unappealing, because they want to see more gesture in the work. My style of painting is much like the religious iconography, which is intentionally meticulously worked to perfection so that you won’t see the brushwork and focus only on the purity of the image. That’s what I want to convey in my images. You have to stop and study it in order to see how I got the final results.

iv) For those who are just starting to explore the flemish painting technique, what are some words of advice that you can offer?

For the flemish technique, the most important aspect is to understand your materials, to get a very good feel of the properties of your mediums, paint and, less importantly, the brushes. The understanding of mediums is extremely important because those are the ones that give off the glaze effect by transparency. Another advice is to look very carefully at other painters, especially the old flemish masters, like the Van Eyck brothers, and study their approach. You can find extremely high-resolution pictures on Google Art Project (cool tip), in which you can zoom extremely close – unlike seeing them in a museum where you have to stand at a distance and don’t really understand what is going on.

v) Are there particular paint brushes or canvas types that you prefer to use because of the flemish technique?

My favourite brushes are the synthetic ones used also for acrylics. I rarely use natural hair, but it is very useful in some cases. I mostly use the brand da Vinci Nova and their models because they’re very versatile and all-rounded. For the natural-haired brushes, I use hog and black sable for blending and glazing. The canvas should be as smooth as possible – I don’t like texture. In this case, a wood support would be very good, but they are heavy, difficult to transport, and prone to damage because of its hygroscopicity (capacity of the canvas to react to the moisture content in the air by absorbing or releasing water vapour), so I stick to canvas which is extremely easy to transport and manipulate in general. You can even mount it on a wall to paint on. It is also much more resistant in time because of its flexibility. Now I use only linen canvas instead of the cotton canvas because it dilates/ contracts much less and so it’s more durable. No matter what support I use, I always re-prime the canvas with extra layers of gesso, which I sand after for extra smoothness. I came to the realization that oil is best suited for my style when I painted a commission work in 2009 and saw the versatility and ease of work of this medium. vi) Many of your compositions are centre-heavy, and you play a lot with perspectives. Is there a particular reason why? I just find it aesthetically pleasing, and it gives me more room for symmetry. I also have a lot of images which are baroque-ish. The more important thing is not the centre focus, but the overall balance. I am now tending towards eccentricity and asymmetrical compositions, which are balanced but not centre-focused. vii) Please tell us about your creative process when you are starting off a brand new piece. First comes the idea, which is sketched very loosely in few variations. Then, I pick one idea and detail it in black and white with pencils or digitally in Photoshop. I never begin a work without the concept already in my head. I get inspiration from my environment – either through media, documentaries, or books – in combination with my thoughts and introspection.

viii) In your opinion, what should art students do in order to start finding their personal style, or preferred painting techniques? What is your advice on balancing commercial work and conceptual work/ passion projects that the artist desires to produce, and what are some of your personal experiences and stories on balancing between the two?

Artists should try to represent their thoughts using their own visual language. I think it’s important, for technical purposes, to pick some very good artists which you aspire to be like in terms of painting technique. Artists should also think a lot about the managing side of their work, but refrain from compromising their creative integrity. They should think about selling their own idea, not to model their ideas in order to have commercial success. I think that if artists stick to their concepts and work very hard, they will succeed in the end, because collectors like masterful and unique art. I don’t try to balance the commercial with the conceptual. I just do my own stuff as unadulterated as possible, focusing on my work and try to figure out how to sell it as it is. I promote my work a lot on social media by posting every day. Although I have sold pieces through galleries and auction houses, I mostly sell directly from my studio. Now I am trying to find a gallery with which I can have a long-term partnership. I am at a point in my career where I think it’s time to put the managing part in someone else’s hands, so I can focus more on my work.

ix) What is the most challenging thing about working with oil, as well as the flemish technique? How long does it take to finish a piece, and how do you manage your time?

Sometimes, the long wait for the oil to dry is painful, but you can balance this by working on multiple canvases at the same time. Also, dust is your greatest enemy as an oil painter. It usually takes between two weeks and three months to finish a painting. Still, I am working now on a large canvas that has surpassed six months and still counting. It is very hard for me to manage my time. I need to get constant motivation, so I need to discipline myself, especially when there is no deadline and I have to finish my whole project in a reasonable amount of time. Sometimes having a decent deadline really helps. Embrace the stress!

A great thank-you to Victor Fota, and images courtesy to the artist himself.